ISCC Concept

International Standard Content Code

by Titusz Pan

The internet is shifting towards a network of decentralized peer-to-peer transactions. If we want our transactions on the emerging blockchain networks to be about content we need standardized ways to address content. Our transactions might be payments, attributions, reputation, certification, licenses or entirely new kinds of value transfer. All this will happen much faster and easier if we, as a community, can agree on how to identify content in a decentralized environment. This is the first draft of an open proposal to the wider content community for a common content identifier. We would like to share our ideas and spark a conversation with journalists, news agencies, content creators, publishers, distributors, libraries, musicians, scientists, developers, lawyers, rights organizations and all the other participants of the content ecosystem.

Introduction

There are many existing standards for media identifiers serving a wide array of use cases. For example book publishing uses the ISBN, magazines have the ISSN, music industry has ISRC, film has ISAN and science has DOI – each of them serving a set of specific purposes. These identifiers have important roles across many layers. The structure and management of these global identifiers strongly correlates with the grade of achievable automation and potential for innovation within and across different sectors of the media industries. Some communities, like online journalism, don’t even have any global persistent identifiers for their content.

Many of the established standards manage registration of identifiers in centralized orhierarchical systems involving manual and costly processes. Often the associated metadata is not easily or freely accessible for third parties (if available at all). The overhead, cost and general properties of these systems make them unsuitable for many innovative use cases. Existing and established standards have trouble keeping up with the fast evolving digital economy. For example nowadays major e-book retailers do not even require an ISBN and instead establish their own proprietary identifiers. Amazon has the ASIN, Apple has Apple-ID and Google has GKEY. The fast paced development of the digital media economy has led to an increasing fragmentation of identifiers and new barriers in interoperability. For many tasks current systems need to track and match all the different vendor specific IDs, which is an inefficient and error prone process.

Advances in data structures, algorithms, machine learning and the uprise of crypto economics allows us to invent new kinds of media identifiers and re-imagine existing identifiers with innovative use cases in mind. Blockchains and Smart Contracts offer great opportunities in solving many of the challenges of identifier registration, like centralized management, data duplication and disambiguation, vendor lock-in and long term data retention.

This is an open proposal to the digital media community and explores the possibilities of a decentralized content identifier system. We’d like to establish an open standard for persistent, unique, vendor independent and content derived cross-media identifiers that are stored and managed in a global and decentralized blockchain. We envision a self-governing ecosystem with a low barrier of entry where commercial and non-commercial initiatives can both innovate and thrive next to each other.

Media Identifiers for Blockchains

Media cataloging systems tend to get out of hand and become complex and often unmanageable. Our design proposal is focused on keeping the ISCC system as simple and more importantly as automatable as possible, while maximizing practical value for the most important use cases — meaning you should get out more than you have to put in. With this in mind we come to the following basic design decisions:

A “Meaningful” Identifier

In traditional database systems it is recommended practice to work with surrogate keys as identifiers. A surrogate key has no business meaning and is completely decoupled from the data it identifies. Uniqueness of such identifiers is guaranteed either via centralized incremental assignment by the database system or via random UUIDs which have a very low probability of collisions. While random UUIDs could be generated in a decentralized way, both approaches require some external authority that establishes or certifies the linkage between the identifier and the associated metadata and content. This is why we decided to go with a “meaningful” content and metadata derived identifier (CMDI). Anyone will be able to verify that a specific identifier indeed belongs to a given digital content. Even better, anyone can “find” the identifier for a given content without the need to consult external data sources. This approach also captures essential information about the media in the identifier itself, which is very useful in scenarios of machine learning and data analytics.

A Decentralized Identifier

We would like our identifier to be registry agnostic. This means that identifiers can be self-issued in a decentralized and parallel fashion without the need to ask for permission. Even if identifiers are not registered in a central database or on a public blockchain they are still useful in cases where multiple independent parties exchange information about content. The CMDI approach is helpful with common issues like data integrity, validation, de-duplication and disambiguation.

Storage Considerations

On a typical public blockchain all data is fully replicated among participants. This allows for independent and autonomous validation of transactions. All blockchain data is highly available, tamper-proof and accessible for free. However, under high load the limited transaction capacity (storage space per unit of time) creates a transaction fee market. This leads to growing transaction costs and makes storage space a scarce and increasingly precious resource. So it is mandatory for our identifier and its eventual metadata schema to be very space efficient to maximize benefit at minimum cost. The basic metadata that will be required to generate and register identifiers must be:

- minimal in scope

- clearly specified

- robust against human error

- enforced on technical level

- adequate for public use (no legal or privacy issues)

Layers of Digital Media Identification

While we examined existing identifiers we discovered that there is often much confusion about the extent or coverage of what exactly is being identified by a given system. With our idea for a generic cross-media identifier we want to put special weight on being precise with our definitions and found it helpful to distinguish between “different layers of digital media identification”. We found that these layers exist naturally on a scale from abstract to concrete. Our analysis also showed that existing standard identifiers only operate on one or at most two of such layers. The ISCC will be designed as a composite identifier that takes the different layers of media identification into consideration:

Layer 1 – Abstract Creation

In the first and most abstract layer we are concerned with distinguishing between different works or creations in the broadest possible sense. The scope of identification is completely independent of any manifestations of the work, be it physical or digital in nature. It is also agnostic to creators, rights holders or any specific interpretations, expressions or language versions of a work. It only relates to the intangible creation – the idea itself.

Layer 2 – Semantic Field

This layer relates to the meaning or essence of a work. It is an amorphous collection or combination of facts, concepts, categories, subjects, topics, themes, assumptions, observations, conclusions, beliefs and other intangible things that the content conveys. The scope of identification is a set of coordinates within a finite and multidimensional semantic space.

Layer 3 – Generic Manifestation

In this layer we are concerned with the literal structure of a media type specific and normalized manifestation. Namely the basic text, image, audio or video content independent of its semantic meaning or media file encoding and with a tolerance to variation. This “tolerance to variation” bundles a set of different versions with corrections, revisions, edits, updates, personalizations, different format encodings or data compressions of the same content under one grouping identifier. A generic manifestation is independent of a final digital media product and is specific to an expression, version or interpretation of a work.

Unfortunately it is not obvious where generic manifestation of a work ends and another one starts. It depends on human interpretation and context. How much editing do we allow before we call it a “different” manifestation and give it a different identifier. A practical but only partial solution to this problem is to create a algorithmically defined and testable spectrum of tolerance to variation per media type. This can provide a stable and repeatable process to distinguish between generic content manifestations. But it is important to understand that such a process is not expected to yield results that are always intuitive to human expectations as to where exactly boundaries should be.

Layer 4 – Media Specific Manifestation

This layer relates to a manifestation with a specific encoding. It identifies a data-file encoded and offered in a specific media format including a tolerance to variation to account for minor edits and updates within a format without creating a new identifier. For example one could distinguish between the PDF, DOCX or WEBSITE versions of the same content as generated from a single source publishing system. This layer does only distinguish between products or “artifacts” with a given packaging or encoding.

Layer 5 – Exact Representation

In this layer we identify a data-file by its exact binary representation without any interpretation of meaning and without any ambiguity. Even a minimal change in data that might not change the interpretation of content would create a different identifier. Like the first four layers, this layer does also not express any information related to content location or ownership.

Layer 6 – Individual Copy

In the physical world we would call a specific book (one that you can take out of your shelve) an individual copy. This implies a notion of locality and ownership. In the digital world the semantics of an individual copy are very different. An individual copy might be distinguished by a license you own or by a personalized watermark applied by the retailer at time of sale or some digital annotations you have added to your digital media file. While there can only ever be one exact individual copy of a physical object, there always can be endless replicas of an “individual copy” of a digital object. It is very important to keep this difference in mind. Ignoring this fact has caused countless misunderstandings and is the source of confusion throughout the media industry – especially in realm of copyright and license discussions.

We could try to define an individual digital copy by its location and exact content on a specific physical storage medium (like a DVD, SSD …). But this does not account for the fact that it is nearly impossible to stop someone from creating an exact replica of that data or at least a snapshot or recording of the presentation of that data on another storage location.

And most importantly such a replica does not affect the original data and even less can make it magically disappear. In contrast, if you give your individual copy of your book to someone else, you won’t “have it” anymore. It is clear, that with digital media this cannot reliably be the case. The only way would be to build a tamper-proof physical device (secure element) that does not reveal the data itself, which would defeat the purpose by making the content itself unavailable. But there are ways to partially simulate such inherently physical properties in the digital world. Most notably with the emergence of blockchain technology it is now possible to have a cryptographically secured and publicly notarized tamper-proof certificate of ownership. This can serve as a record of agreement about ownership of an “individual copy”. But is does not by itself enforce location or accessibility of the content, nor does it prove the authorization of the certifying party itself or the legal validity of the agreement.

Algorithmic Tools

While many details about the ISCC are still up for discussion we are quite confident about some of the general algorithmic families that will make it into the final specification for the identifier. These will play an important role in how we generate the different components of the identifier:

- Similarity preserving hash functions (Simhash, Minhash …)

- Perceptual hashing (pHash, Blockhash, Chromaprint …)

- Content defined chunking (Rabin-Karp, FastCDC …)

- Merkle trees

ISCC Proof-of-Concept

Before we settle on the details of the proposed ISCC identifier, we want to build a simple and reduced proof-of-concept implementation of our ideas. It will enable us and other developers to test with real world data and systems and find out early what works and what doesn’t.

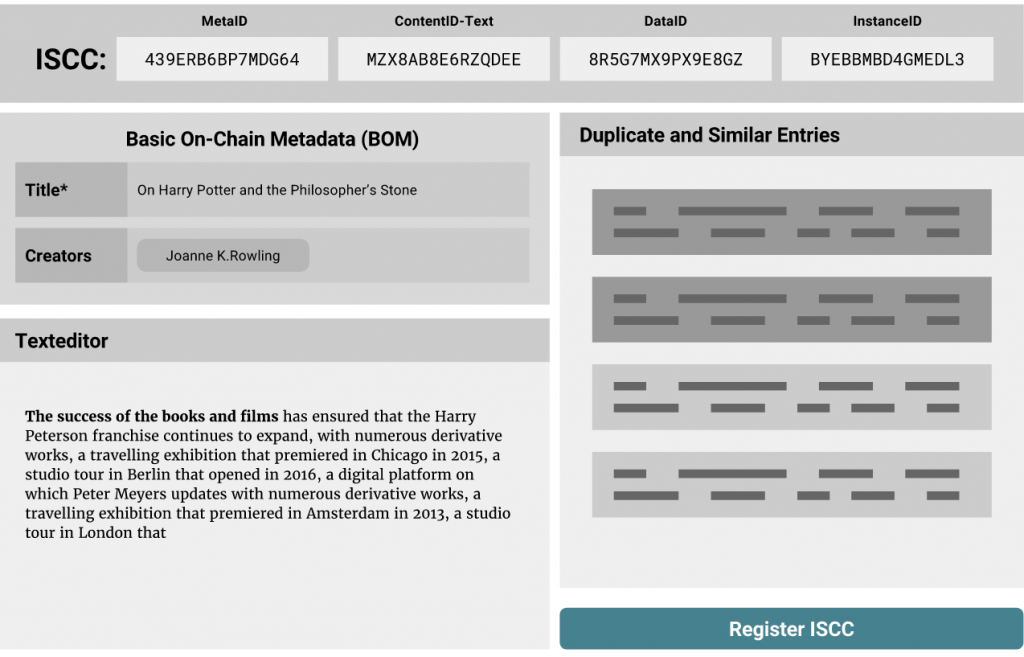

The minimal viable, first iteration ISCC will be a byte structure built from the following components:

MetaID

The MetaID will be generated as a similarity preserving hash from minimal generic metadata like title and creators. It operates on Layer 1 and identifies an intangible creation. It is the first and most generic grouping element of the identifier. We will be experimenting with different n-gram sizes and bit-length to find the practical limits of precision and recall for generic metadata. We will also specify a process to disambiguate unintended collisions by adding optional metadata.

Partial Content Flag

The Partial Content Flag is a 1-bit flag that indicates if the remaining elements relate to the complete work or only to a subset of it.

Media Type Flag

The Media Type Flag is a 3 bit flag that allows us to distinguish between up to 8 generic media types (GMTs) to which our ContentID component applies. We define a generic media type asbasic content type such as plain text or raw pixel data that will be specified exactly and extracted from more complex file formats or encodings. We will start with generic text and image types and add audio, video and mixed types later.

ContentID

The ContentID operates on Layer 3 and will be a GMT-specific similarity preserving hash generated from extracted content. It identifies the normalized content of a specific GMT, independent of file format or encoding. It relates to the structural essence of the content and groups similar GMT-specific manifestations of the abstract creation or parts of it (as indicated by the Partial Content Flag). For practical reasons we intentionally skip a Layer 2 component at this time. It would add unnecessary complexity for a basic proof-of-concept implementation.

DataID

The DataID operates on Layer 4 and will be a similarity preserving hash generated from shift-resistant content-defined chunks from the raw data of the encoded media blob. It groups complete encoded files with similar content and encoding. This component does not distinguish between GMTs as the files may include multiple different generic media types.

InstanceID

The InstanceID operates on Layer 5 and will be the top hash of a merkle tree generated from (potentially content-defined) chunks of raw data of an encoded media blob. It identifies a concrete manifestation and proves the integrity of the full content. We use the merkle tree structure because it also allows as to verify integrity of partial chunks without having to have the full data available. This will be very useful in any scenarios of distributed data storage.

We intentionally skip Layer 6 at this stage as content ownership and location will be handled on the blockchain layer of the stack and not by the ISCC identifier itself.

A first experimental prototype of the ISCC idea is in development on Github.